Laurel Daen headshot

Laurel Daen headshot

The term ableism is said to have roots in the 1980s disability rights movement in the United States, but historian Laurel Daen says the behaviors and beliefs at the root of the word date back to the founding of the nation, and even before.

“Ableism is a system of power and privilege that hierarchically ranks those with perceived able bodies over people with disabled bodies. Ableism teaches us that body and mind normativity is preferrable,” said Daen, assistant professor of American studies. “Ableism is also discrimination against disabled people based on a belief that these people are less than or not worth the same as able-bodied people, and it results in oppressions and marginalization.”

Such attitudes are known to have existed in Early Modern English and Colonial American laws and policies. As the new republic was created, men and women with disabilities were not seen as citizens and were not allowed to vote, marry, own property, or settle in certain towns.

As the United States marks 34 years since the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), Daen cautions that the United States still has a long way to go in creating welcoming spaces for people who have disabilities. “In the same way that racism and sexism have existed for millennia, ableism certainly still exists today,” she said. “It’s this big amorphous thing that exists structurally, interpersonally, and internally. For example, you might hold ableist ideas about yourself.”

The ADA has ushered in a great deal of opportunity and access for the disabled community in everyday activities, but the guidelines are not always followed. Neither, says Daen, can the law remove the stigma of disability or deeply held prejudices that non-disabled people might hold. As a result, physical and cognitive impairments may be perceived as a negative experience and people with those impairments may be ignored, excluded from activities, presumed to be helpless and unable to make decisions, or coddled.

It is possible, however, to become less ableist in our behaviors and beliefs. Daen says the simplest way to do so is by simply engaging with disabled people. Campus organizations like ND Ability and Access-ABLE ND offer great opportunities to attend a meeting or event and support their initiatives. Service programs like ND Bridge often work with community organizations that serve constituents with intellectual, developmental, or physical disabilities.

There are also classes in the College of Arts and Letters’ Disability Studies program, like Disability at Notre Dame–-one of the courses Daen has taught. In the class, students were given $5,000 to spend on campus to enhance accessibility. “I’ve taught it twice. Students have great project ideas—everything from increasing signage in the dining halls about food allergies to social media campaigns that raise awareness about mental health. The biggest project has been trying to have American Sign Language (ASL) recognized as a foreign language on campus,” said Daen.

Most importantly, if you’re advocating for accessibility and inclusion, listen to the voices and lived experiences of the disabled community. “Disabled people have wisdom and knowledge about their bodies and minds that supersedes other types of knowledge,” you might gain through theoretical concepts, Daen said. “The disability rights movement is centered on the idea of ‘nothing about us without us.’ Disabled people should be leading some of these initiatives. They are the experts.”

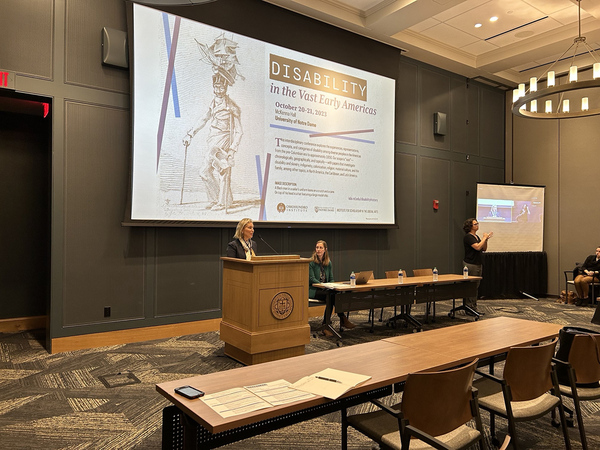

Daen took this advice to heart when organizing the Disability in the Vast Early Americas conference in October 2023. The hybrid event, believed to be the first disability history conference in more than 20 years, was held on Notre Dame’s campus. Daen and other organizers worked hard to ensure that they created a space that felt comfortable for everyone and that allowed people to engage at all capacities. “We talked to people and asked what they would need, and that conversation led us to create rest spaces where people could go to take a break during and between sessions,” she said. Participants also wore masks in consideration of people who had immunodeficiencies. Presenters were asked to use plain language and speak slowly so their content would be more accessible to someone with a cognitive or hearing disability. And visual materials were created in high contrast for better readability by someone with a visual impairment.

The hybrid format allowed participants with issues traveling to participate, and the video setup allowed their faces to be shown in large detail so it felt like they were in the room along with the in-person attendees. Organizers also made the decision to offer ASL interpretation whether or not a conference participant asked for it.

It wasn’t an easy or inexpensive process, but Notre Dame Studios and University Enterprises and Events were receptive to all of the organizers’ ideas and helped to make the event a success for the 49 presenters and more than 130 people who attended. One person told Daen it was the most accessible conference they had ever been to.

For the 2024-2025 academic year, Daen is working to finalize her book, tentatively titled “Capacity for Citizenship: Disability, Rights, and Resistance in the Early United States.” A continuation of her dissertation, the book details “how exclusions were imagined, implemented, and enforced with repercussions for disabled people” in early America. “There’s a lot of research about certain groups of people, but I feel like disabled people are left out and often overlooked. So I’m really happy to reinsert [disabilities] into the conversation when we can,” she said.

Originally published by at diversity.nd.edu on July 25, 2024.