Kathleen Sprows Cummings

Kathleen Sprows Cummings

In new research, Kathleen Sprows Cummings — University of Notre Dame associate professor of American studies and director of the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism — chronicles how canonization, or the intricate process of naming someone a saint, prompted a minority religious group to define, defend and celebrate its American identity.

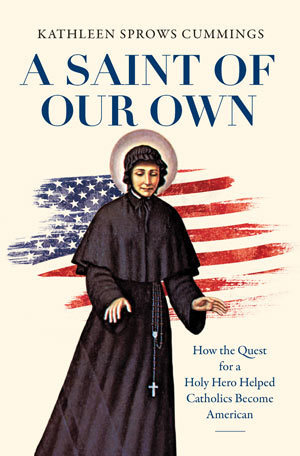

Cummings’ A Saint of Our Own: How the Quest for a Holy Hero Helped Catholics Become American is the first study of multiple causes for canonization within a United States context. In addition to cataloging a variety of historical figures elevated as models of Catholic virtue and American ideals, Cummings sets out to “bring into focus U.S. Catholics’ understanding of themselves both as members of the Church and as citizens of the nation, and to understand how those identities converged, diverged and changed over time.”

While holiness as a concept may transcend time and space, it is lived out by people who are inseparable from the cultures and contexts in which they lived. U.S. Catholics were without a saint born on their American soil until the 1975 canonization of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, and Cummings claims this void left many American Catholics feeling “not only spiritually unmoored but also periodically subject to the condescension of their transatlantic counterparts.”

Cummings’ study of transnational, typically complex and often-labyrinthine causes for canonization includes Seton, Kateri Tekakwitha, Frances Cabrini, John Neumann and many others whose causes are failed, forgotten or still underway.

She also considers the ways shifting societal values shaped causes for canonization as Catholics settled into the American mainstream. The United States still does not have a patron saint, Cummings points out, largely because of a perennial dissonance at the heart of American Catholic experience.

“U.S. Catholics belong to a Church that measures change in centuries, but live in a culture that changes easily and quickly,” said Cummings, who is also an associate professor in the Department of History. “Even in the cases where a cause for canonization moved rapidly in Rome, the interval between a cause’s introduction and its successful conclusion could seem an eternity by American standards.”

According to Cummings, by the time the favorite prospective saints of one generation of U.S. Catholics had been canonized, the next generation had a new American story to tell about themselves — and they searched for saints who could help them tell it.

A well-known expert on 19th- and 20th-century American Catholicism, Cummings has published extensively on the lives and work of Catholic sisters, and the complex relationship between gender and Catholic hierarchy.

In “A Saint of Our Own,” Cummings highlights the role of female petitioners who initiated and shepherded the causes for canonization for people they believed worthy of sainthood. Until 1983, canon law required women wanting to petition for a cause of canonization to do so through a male proxy.

“Church leaders have long used models of female sanctity to control and contain women — and Catholic women have, conversely, cited the example of female saints as justifications for expanding gender roles,” Cummings writes.

In tracing petitioners’ causes, Cummings explores how more-traditional expectations of female behavior shaped definitions of holiness. The story of canonization in America is also the story of the Church’s interlocking systems of power: men over women, clergy over laity and hierarchy over clergy. The story she tells is timelier than ever, given how these power relationships contributed to the clergy sex-abuse crisis, the latest revelations of which are presently roiling the Catholic Church.

In April, Cummings received the Pedro Arrupe, S.J., Award for Distinguished Contributions to Ignatian Mission and Ministry from the University of Scranton, her undergraduate institution. University of Scranton President Rev. Scott R. Pilarz, S.J., presented the award, praising Cummings for her scholarly career and her public advocacy for major reforms in the Catholic Church in the wake of the sexual abuse scandals. Cummings will also deliver the University of Scranton’s undergraduate commencement address and receive an honorary degree on May 26.

Additionally, Cummings co-chaired Notre Dame’s Research and Scholarship Task Force, a committee formed in response to the sex abuse crisis that offered expertise and recommendations to help the Catholic Church move toward healing and constructive change.

Originally published at news.nd.edu.